BORDEAUX 2022: VINTAGE OVERVIEW

Share

The 2022 vintage broke records in France for its hot, dry conditions – but the wines it produced are far from solar. Fresh from a week spent digging into the vintage with producers and tasting the wines, Sophie Thorpe reports on the remarkable year and the wines it produced

There’s been a lot of hype about 2022. But is it as good as people have been saying? Well, the short answer is yes – and no. This is a vintage that is much more complicated than a simple declaration of greatness, but there are some immense wines – some of the best we’ve ever tasted en primeur.

It’s fascinating how much attitudes have changed since conversations in October. When we visited after the harvest, while the ferments were still bubbling away, there was some concern about the freshness of the wines – with Pierre-Olivier Clouet at Ch. Cheval Blanc in particular nervous about the high pH – but, six months on, those worries are a distant memory.

As Edouard Moueix (of Jean-Pierre Moueix) told us, “We can’t really explain why the wines are like this.” And he wasn’t alone – almost every vigneron in the region has been pleasantly surprised by the freshness in the wines from what was one of the hottest and driest years on record. Despite that, we’ll do our best to explain the conditions and actions that produced these remarkable wines.

The growing season

We covered the growing season briefly after our visit in October last year, however – having now spoken to a wider range of producers around the region – there is much more to add on what was a long and trying season for the region’s vignerons. As Saskia Rothschild pointed out, “I think that the vines were less stressed than we were.”

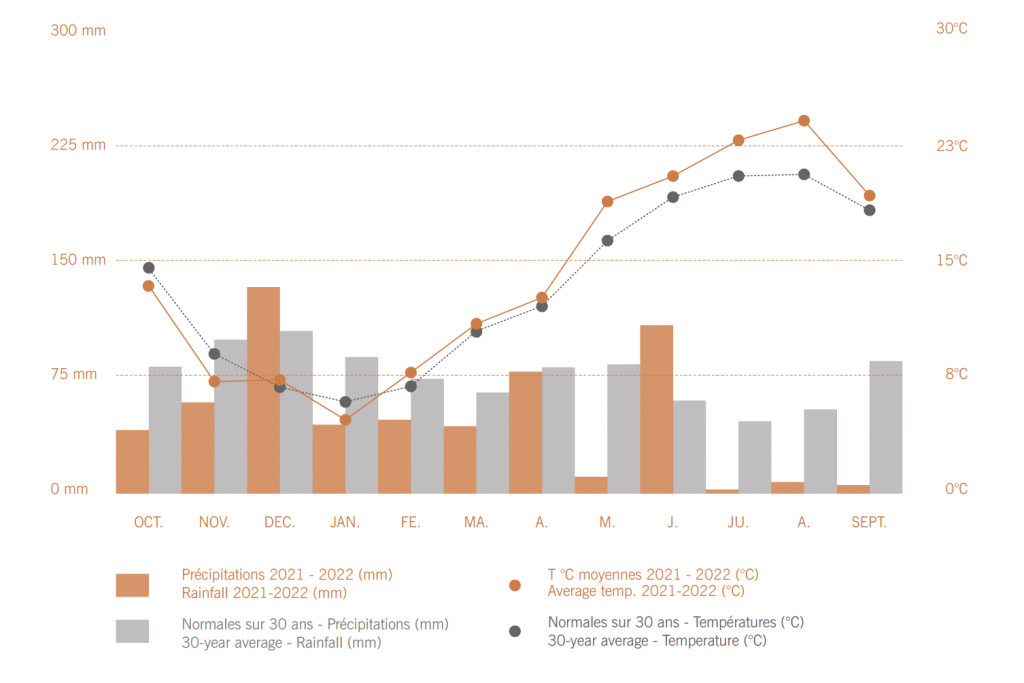

The wet 2021 vintage laid the groundwork for 2022, ensuring the soils were replenished. Although some producers reported a dry winter with the region’s “jalles” (streams) running dry, December 2021 had higher rainfall than average – something that was essential as each month thereafter built up a growing deficit. Between November and March, vineyards received around 100-200mm less rain than normal, but from April onwards the drought really struck – peaking in July with a mere 3mm rain in the region.

A graph showing rainfall and temperatures for the 2022 growing season, alongside the 30-year averages at Ch. Lynch-Bages, Pauillac

Budburst was early, starting in late March with the mild weather. Early April brought frost (between 1st and 6th), but it had little impact on most producers, who are now well versed in the use of wind fans, heaters and bougies (candles). This was followed by good weather that several vignerons noted helped the vines recover quickly.

Flowering was even in mid-May, with temperatures already feeling like midsummer, and the first heatwave hitting in early June. There were significant thunderstorms in June, bringing up to 150mm rain over the month – offering much-needed relief to the water-starved vines, even if it wasn’t enough to replenish the water table fully. On 20th June, however, a hailstorm swept through the northern part of Saint-Estèphe, devastating yields for some producers. Fortunately it was very localised – with Cos d’Estournel, Montrose and Calon Ségur not seeing any significant damage, for example. Beau-Site wasn’t so lucky, however, losing over 50% of their crop to the combined effects of hail and frost earlier in the season.

The high temperatures continued, arriving in several waves. July was particularly dry (with just 3mm rain, as mentioned), but August saw a sprinkling of rain in some areas. At Ducru-Beaucaillou, they highlighted that the oceanic mists helped bring some moisture, but in general there was very little rain in this latter part of the growing season – Ch. Margaux saw just 40mm from June to harvest. Noëmie Durantou Reilhac (of Ch. l’Eglise-Clinet) explained how the vines were starting to look a little less happy by the end of July, with the leaves just starting to droop, but showers in August – a mere 15-20mm across the month – provided the tiny sips of water that allowed the vines to make it to the finish line of their marathon season.

Early morning at Calon Ségur in Saint-Estèphe, where the more clay-rich soils produced some fabulous wines in 2022

Picking for the whites started in mid-August, with the reds following from the very end of the month, making it the earliest on record for several addresses. For Ch. Mouton Rothschild, it was the earliest harvest since 1893. In general, harvest dates – and approaches – varied quite significantly – with the start of picking ranging for reds from 29th August right through to 16th September.

With the hot, dry conditions meaning there was practically no disease risk, some producers took their time bringing fruit in – making it the longest harvest ever for the likes of Léoville-Poyferré or Ducru-Beaucaillou. Others argued it was necessary to bring the grapes in quickly before too much sugar accumulated. Damien Barton-Sartorius (Ch. Langoa and Léoville Barton) mooted that some people had picked too early, fearing the high sugar and resulting alcohol levels, but therefore sacrificing phenolic ripeness – producing wines with hard tannins.

Lilian and Damien Barton-Sartorius in their new winery, clutching their impressive 2022s which are stars of the vintage

Several producers did multiple passes through the same plots (a practice more common with the region’s botrytised sweet wines), often separating younger and older vines, as at Pichon Baron. Of course, much depended on the size of picking team at an estate’s disposal, as well as the size and spread of their vineyards. The Borie-Manoux estates were able to use a larger team than normal to harvest, with 20 additional workers to bring in the fruit exactly when they wanted.

Edouard Moueix noted how the hot, windy September conditions meant they were losing 1-3% of the berry weight each day. There was a little rain at the end of September – and some people picked Cabernet after this, benefiting from precious extra juice.

Overall volumes are down, around 10% below the 10-year average across the entire region. For many estates, especially on the Left Bank, the yields were actually around the same or even lower than the mildew-impacted 2021 vintage – dipping as low as around 20hl/ha at some addresses (versus a more normal 40-42hl/ha). With the dry conditions and the Left Bank’s predominantly gravel soils, the berries were particularly small – with a high skin-to-juice ratio meaning the volume of liquid released was very low. Ch. Palmer told us the average berry weight in 2022 was 25% lower than their 10-year average.

Yields tended to be healthier on the Right Bank, normally sitting around the average for producers – with the clay and limestone soils holding more water. The most severe losses were for the white wines, both due to a larger impact from the April frost and the hot, dry conditions; at Ch. Margaux, for example, the yield was just 15.5hl/ha for Pavillon Blanc.

In the vineyard at Ch. Lafite-Rothschild, Pauillac

Given the heat of the year, the natural comparison for vignerons was to 2003 – however there are several elements that ensured 2022 wasn’t a repeat of that year. The 2003 vintage was the first of its kind, taking producers by surprise, with many de-leafing, not being ready to farm, pick or manage fruit that ripe. The resulting wines – for the most part – haven’t stood the test of time.

But, over the last two decades, there has been a revolution in the vineyards and wineries of Bordeaux, with a total transformation in terms of the level of precision and knowledge, with investment that has really paid off. It’s a different place today. And, with the experience of not just 2003, but many other vintages (2005, ’09, ’10, ’15, ’18, ’19, ’20), vignerons are now au fait with warm conditions.

In addition to these significant developments, the conditions in 2003 were a shock – coming in one three-week-long “canicule” (heatwave), with the high temperatures sustained overnight. In 2022, the season started hot and dry – something which many producers argued helped the vines to adapt to the conditions, with many talking about the vines being able to prepare for a marathon. When the more severe heat did arrive, it came in spikes (generally four or five different heatwaves, depending on where producers were). Although there were a similar number of hot days to 2003 (with 45 days over 30˚ C), they were more spread out. Importantly, as Daniel Cathiard at Smith Haut Lafitte, among other producers, noted, cooler nights allowed the vines to recuperate (hitting a maximum 20˚C), as well as the essential refreshment of the June rainfall.

Exploring the conditions of the remarkable year with Ch. Cheval Blanc's Pierre-Olivier Clouet

It’s worth mentioning that there were significant fires to the south of Bordeaux in 2022, with evacuations as flames engulfed pine forests in the Landes, closest to Graves and Sauternes. Despite initial fears, the wind direction meant that smoke taint was fortunately not an issue for producers – as extensive testing and everything we tasted confirms.

How did producers handle the 2022 vintage in the vineyard?

The 2022 vintage, while not easy, didn’t require a huge amount of work in the vineyard. After 2021, its hot, dry conditions made for a gloriously disease-free crop – however they did pose their own challenges.

Gone is the era where the Bordelais stripped their vines bare, praying the grapes would ripen sufficiently before the rains came. In 2022’s hot, dry conditions, almost all producers avoiding de-leafing – leaving a thicker canopy to shade the grapes from the blazing sun and prevent them from burning. Pierre-Olivier Clouet at Cheval Blanc highlighted that the hot, dry start to the season meant the vines didn’t grow secondary shoots, and the canopy was naturally small – meaning there was less evapotranspiration, sugar accumulation and therefore smaller berries.

Several producers employed “sunscreen” of sorts, spraying the leaves and/or fruit – with kaolin (a type of white clay) the most common option. Ch. Pontet-Canet Technical Director Mathieu Bessonnet explained that they used it across their vineyards, having to apply it three times to some blocks; while the team at Calon Ségur found they had no need to use it at all this year. At Ducru-Beaucaillou, they used talc. At Les Carmes Haut-Brion, Guillaume Pouthier used both talc and montmorillonite (another type of clay), keeping the temperature inside the berries 5-10˚C lower than they would be without this shield.

The impressive avenue that leads to Ch. Margaux

After the challenges of 2021, organic and biodynamic producers were rewarded, with little disease pressure making it an easier year to farm with these methods. At Pontet-Canet, Bessonnet explained that they used chamomile to help relieve the vines’ stress, something which he felt was key – a sentiment echoed at Smith Haut Lafitte, who also used yarrow. Producers working this way often pointed to their farming methods as the key to the freshness in their wines.

Old vines, with deeper root systems, handled the conditions better – with young vines sometimes showing signs of stress much earlier, and some even shutting down, often the first to be picked and generally producing lower yields. At Ch. Lafite Rothschild and Ch. Duhart Milon, they started picking the younger vines that were starting to show the effects of the season from 31st August, however they found the fruit wasn’t up to scratch and didn’t end up using it in the final blends. At Ch. Brane-Cantenac, Henri Lurton found they had to do a green harvest for their younger vines to help them survive the season, with the August rains arriving too late to allow them to avoid dropping fruit.

It was also a year where each terroir was put to the test. Those with clay and limestone soils – that held more water for the vines to draw upon – generally saw better yields, with the gravel-dominant Left Bank seeing lower volumes with its free-draining soils. Pockets of more clay-rich soils, such as Saint-Estèphe, also benefitted, with some superb wines from the appellation this year.

Among the vines at Ch. l'Evangile in Pomerol

Whatever their soil composition, producers worked to harness the little moisture in their soils. Maylis Marcenat at Ch. Clos de Sarpe spread manure after the 2021 vintage, something that she felt really helped (and will now be an annual activity). Many producers – such as La Conseillante – seeded cover crops and then crimped or rolled them to leave a “thatch” between the rows, retaining humidity and keeping soil temperatures cooler.

Another common option was “griffage” – surface tilling, breaking just the topsoil (5cm or so) to help the soils retain water, as at Lafleur, Smith Haut Lafitte and Feytit-Clinet. At Les Carmes Haut-Brion, Guillaume Pouthier highlighted that it was important to work the soil at night, from 7pm to midnight, when the temperatures dropped and the moon drew the water to the surface.

With the unusually dry conditions, the appellation bodies permitted irrigation in some areas (Pessac-Léognan, Saint-Emilion and Pomerol). Few of the producers we visited seemed to take advantage of this option – although Ch. Clinet did. For any estates without a well, irrigating is expensive – having to pay for any water used. Maylis Marcenat at Clos de Sarpe explained that the cost for just her tiny plot of baby vines was around €4,000.

Jacques Thienpont of Le Pin, standing at attention during our tasting

As Jacques Thienpont of Le Pin told us, it was a year where producers felt “the mark of climate change”. But, despite these significantly challenging conditions, the vines were green until the very end of the season – still looking vibrant when we visited in October. “The days of Touriga Franca and Tinto Roriz are not yet here,” said Jean-Guillaume Prats of Domaines Delon (owners of Ch. Léoville Las Cases).

How did producers handle the vintage in the winery?

Some producers argued that the fruit was so good in 2022 that winemakers were almost redundant – however, from our tastings, it’s the skill of the vigneron at the helm of each estate that separates the very best wines.

Unlike in 2021, the fruit harvested was beautifully healthy in 2022 – but sorting was key for different reasons, removing sunburnt or shrivelled grapes, particularly those that were unripe but had dried on the vine. As Damien Barton-Sartorius noted, if these latter berries ended up in the tank, they would rehydrate in the must and release hard tannins. At the Barton estates, they did a pass through the vines dropping any shrivelled bunches prior to harvesting, and then their vibrating sorting table caught any that remained.

Looking out across the gardens to the vineyards of Saint-Emilion at Ch. Ausone

With the thick-skinned berries, it was key that tannins were managed carefully. While almost every producer agreed on this being an important factor, how to manage them differed around the region.

Cold soaks were more common this year, as at Figeac, Beychevelle and Léoville-Poyferré. The team at Haut-Bailly was particularly thankful for the cool rooms in their new winery (finished in 2020), allowing them to chill the fruit overnight before vinification.

There were two main schools of thought when it came to extraction – choosing to be more aggressive (as at Palmer, Feytit Clinet and the Durantou estates), or to be more gentle.

“We decided to take advantage of that concentration,” the team at Ch. Palmer told us. Noëmie Durantou Reilhac explained that with the amazing quality of the tannins in the skins and pips, she wasn’t worried about these becoming hard – but wanted to extract while the temperatures were cooler (around 21˚C, and before there were high alcohols, changing the nature of the tannins). She is looking for purity of fruit and finesse in her wines, so although she worked the must more, it spent just two to five days on skins after fermentation had finished to avoid losing any freshness.

One of the prettiest estates in Bordeaux, the Chanel-owned Ch. Rauzan-Ségla

It's become fashionable for producers to talk about “infusion” rather than extraction, and the majority of estates pointed to this gentle approach to being key to tannin management. Some felt that pump-overs rather than punch-downs were preferable (such as Marquis d’Alesme and Le Pin), others the opposite (such as at Domaine de Chevalier); some felt shorter macerations were better, others favoured longer with less extraction. Many used cooler temperatures, with Cheval Blanc, for example, starting the maceration at just 15-16˚C, to help preserve the aromas.

For those who opted for gentler maceration, they often included higher proportions of press wine. At some estates on the Left Bank, they used the highest percentages ever – 16% at Brane-Cantenac or 17% at Rauzan-Ségla, for example. Charles Fournier at Ch. Mouton Rothschild pointed out that press wine is the key to building mid-palate density. By contrast, however, Durantou Reilhac cautioned that it’s easy to add too much – as it can be “gras” (a little fat), and level the aromatics. At the other end of the spectrum, Cheval Blanc doesn’t ever use any press wine.

Guillaume Pouthier – who is the poster-boy for whole-bunch fermentation in the region – used record-high percentages this year, with 70% for the Grand Vin at Les Carmes Haut-Brion. Although it can increase the pH, it helped reduce the alcohol. They harvested at 14.6% potential alcohol, but with the combined impact of the whole-bunch (via osmosis with the water in the stems) and native yeast (which is less efficient at converting sugar to alcohol), the final alcohol level was only 13.5% (and the pH a modest 3.6).

Tasting Joséphine Duffau-Lagarrosse's second vintage at her family estate, Ch. Beauséjour Duffau-Lagarrosse

With the warmth of the year, sugar levels in the grapes, and therefore alcohol levels in the final wines are generally high. This could pose a challenge for fermentation – indeed, Le Pin had to resort to using commercial yeast to finish their ferments for the first time. These alcohol levels, combined with generally low acidity and high pH levels, mean that some wines are fragile. As Pierre-Olivier Clouet said of Cheval Blanc (with the highest-ever pH at 3.86) this year, “It’s a bomb.” The wines need to be guided through to bottling, to avoid microbial spoilage, volatility and Brettanomyces.

The approach for élevage is generally the norm, with a few producers choosing to tone down the use of new oak. With the density of fruit in the wines, it was incredibly rare for the oak to stand out at all, even at this early stage.

What are the 2022 wines like?

Bordeaux’s winemakers are as confused as anyone as to how the conditions outlined above produced the wines they did. They combine remarkable depth of fruit, with aromatic finesse, high levels of ripe tannins and surprising freshness. Although these are concentrated, rich wines, the very best have this remarkable sense of weightlessness that makes them seem almost ethereal. Those who have mastered the vintage captured the fruit, yet retained glorious freshness and remarkable delicacy that seems almost impossible.

The alcohols are generally high – with the lowest at 13.5%, and some reaching above 15%. It was rare, however, for even the punchiest of ABVs to stand out, there is such a weight of fruit that the alcohol is beautifully integrated. At Ch. Margaux, for example, it’s the highest alcohol they’ve ever seen – with 14.5% for the Grand Vin (previously only hit 14%), but this is countered by what is – as Aurélien Valance noted – the “most powerful, dense and concentrated wine [they’ve] ever produced”.

In the vineyard at Ch. Belle-Brise, Pomerol

The most challenging area is acidity. The hot weather degraded malic acid, and the pH levels can be high – reaching up to 3.9 for the reds. Despite what the numbers sometimes suggest, however, there are extremely few heavy wines, with the vast majority beautifully vibrant. “The mystery of this vintage is its freshness," Vincent Millet of Calon Ségur told us. There’s often a pleasing saline, savoury, almost bitterness that comes through on the finish, especially on the Left Bank – adding to the freshness in many instances, and avoiding these being fruit bombs. Guillaume Pouthier cautioned against the sense of freshness in some wines – feeling it’s the “energy of vinification” that is coming through, and that wines with more than 3.6 or 3.7pH won’t last in the cellar.

While it’s easy to be mesmerised by the year’s generous fruit, we found that the very best wines have seamless, fine-boned structure – high levels of tannins but with such silken texture that they don’t dominate. Indeed, when you look at the IPT numbers (the Total Polyphenol Index that has started cropping up more in analysis from producers and critics), they are remarkably high – sometimes the highest-ever for estates, such as at Calon Ségur (with 78). At Les Carmes Haut-Brion, the IPT is approaching 100 – yet they are so smooth that the wine is almost irresistible now.

There are undoubtedly some big wines that will need time – packed with fruit, alcohol and tannin. For the most part, these wines are blockbusters, but well-balanced and there’s little doubt about their ageability, but they need cellaring before they’ll be approachable.

As we’ve hinted at, however, the vintage isn’t entirely homogenous. There are no bad wines, but there are a handful that don’t hit the heights of the greatest wines this year. Although they are few and far between, there are wines where the alcohol or tannin stands out, with not quite sufficient acidity – these wines represent a bolder style that undoubtedly appeals to some palates, but don’t have the finesse of those that excelled in 2022. When it comes to knowing which these, it’s not as simple as saying these are limited to particular appellations, levels in their classification or picking dates, unfortunately, so it will be important (as ever, really) to pick and choose in the vintage. We sent our largest-ever team out to the region, and it was incredibly important to be there to taste these differences – so that you can use both their advice, as well as those of the critics.

Diving into the detail of the year with Guillaume Pouthier at Ch. les Carmes Haut-Brion

In general, the Left Bank offered a little less consistency versus the Right, with Margaux the most variable appellation. Yields were generally lower on the Left as well, with the free-draining gravelly soils. On the Right Bank, yields were mostly more generous and the results more consistent. Although Merlot performed well, we found that the best wines were those with a touch of Cabernet Franc that restrained Merlot’s exuberance – bringing a touch more precision and freshness. These are, however, generalisations – and there are exceptions. At some addresses, the second wines have seriously over-performed (such as La Dame de Montrose, Carruades de Lafite and Ségla), at others they seem less impressive than normal – again, this needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

It's certainly a year where the best sites shone. Limestone was a godsend, allowing producers to retain freshness with great ease. At Clos de Sarpe, the wine is a mere 3.3pH (when some of their neighbours are sitting at 3.9). Charles Fournier at Ch. Mouton Rothschild feels that “the style of each château is even more obvious” this year, accentuated by the extreme conditions.

But for many, it’s a year that proved the region can handle climate change – a year that vouched for Merlot’s prowess. “Despite the heat, despite the dryness, Bordeaux is still able to produce classic wines,” said Fournier.

Tasting at Ch. Clos de Sarpe, where the wine has amazing freshness thanks to their special terroir

And so to the comparison game. Each vintage is, in the eyes of a vigneron, unique – and it’s especially the case with 2022, which has confounded producers. They all agree, however, that this is a year for the history books. At Vieux Château Certan, Alexandre Thienpont dared – for the first time ever – to declare it “un grand vin”, while the normally modest and quiet Henri Lurton (Ch. Brane-Cantenac) had not shame in declaring it the best vintage he’s ever made, feeling it’s as legendary as 1961.

“1945?” Damien Barton-Sartorius half-joked in response to the question of which vintage 2022 reminded him of. It’s a legendary vintage for Léoville Barton, and although he wasn’t entirely serious, he feels it is a great year for their wines – sitting in the league of 2016 and 2019, which he opened for us to taste alongside. He also wasn’t the only producer to point to 1945, with Jacques Thienpont suggesting it, or 1947, as possible comparisons, with a more elegant version of 2020 in more recent memory. Climatically, the Domaines Delon team pointed to 1870. The 1982 vintage was another that cropped up several times, with a sense among producers that the wines are set to have a similar trajectory given the balance on show.

Although the conditions were hot and dry, many producers were clear that it isn’t a “solar” vintage – not like 2009, 2010 or 2015. At Marquis d’Alesme, Marjolaine de Coninck felt it is closest to 2016 – offering amazing balance, with acidity, tannin and sweetness of fruit. Jeremy Chasseuil at Ch. Feytit-Clinet pointed to 2016 or 2019, while Vincent Millet at Calon Ségur suggested it could sit somewhere between 2018 and 2020, but more concentrated.

For us, 2016 and 2019 are the best comparisons, showing a balance of concentration, freshness and precision, yet the best wines also display an approachability and ethereality that exceeds the finest wines in either of these vintages. At the top end, it really is a very special year.

It was an incredibly exciting vintage to taste and talk about, and really is as unique as producers said. Seemingly easy on the surface, it is all the very fine detail that has defined whether producers made good or great wines this year. With the right attention in the vineyard and winery, as well as a good site, the 2022 vintage produced exceptional wines – wines with balance and finesse, yet also the compact concentration that will allow them to age for decades. The challenge, with the finest wines, may be resisting them until then.

Bordeaux 2022: the vintage in summary

- Record-breakingly hot and dry growing season

- Although fears were that it would be like 2003, it very much wasn’t

- Significant diurnal variation and rain in June brought relief

- Old vines were a significant advantage

- Yields are down by as much as 40%, lower on the Left Bank and especially for the whites

- Water-retaining clay and limestone soils were helpful, and allowed for better yields

- Small berries and thick skins meant tannin management was key

- Frequently compared to 2016, 2019 and 2020, as well as 1945 and 1982

- While this is a very good vintage, it is not totally homogenous

- The best wines are exceptional – concentrated and structured, yet with weightless power and wonderful freshness

Next week, we’ll publish our breakdown of the vintage by commune, with recommendations for each.